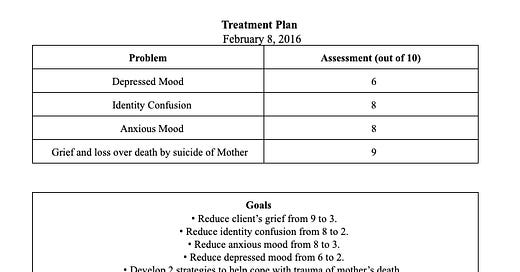

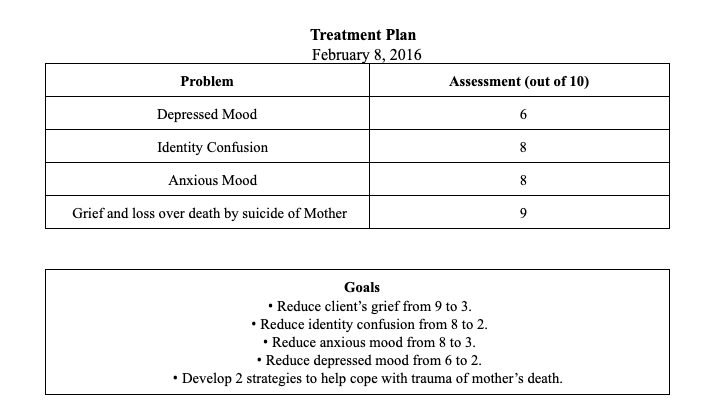

On a blustery February day fifteen months after my mom dies, I find myself in the attic of a refurbished house-turned-counseling office in a residential neighborhood of St. Paul. Sitting in a stiff, blue wingback chair, my eyes quickly scan the watercolor paintings on the pale walls, assessing the curated serenity. Katie the Counselor sits five feet away in a black desk chair with wheels. She works her way down a checklist, lobbing questions my way, each requiring a numerical answer. I slump back into the chair, irritated but too tired to resist. I keep my eyes fixed on the flame of the artificial candle, lobbing answers back to her, doing my best to speak her language.

In the last week, how would you rate your anxiety—on a scale from one to ten?

Um, Seven.

In the last week, how would you rate your sadness—on a scale from one to ten?

Eightish.

Katie the Counselor is about fifty with naturally curly blondish hair and a practical sensibility, like she grew up on a farm. She wears a funky purple scarf and Dansko clogs. Her back is turned toward me as she types my answers into her desktop computer. I do not know it yet, but she is beginning to write my treatment plan. Katie the counselor uses the first fifteen of our fifty minutes together on this assessment. But who’s counting?

The Gnugu Yimithirr tribe of north Queensland in Australia have only a few words for numbers: nubuun (one), gudhirra (two), guunduu (three or more).

Numbers Katie the Counselor Did Not Ask Me About

The number of childhood soccer games I played with Mom as my coach: 78.

The number of violin concerts, basketball and soccer games Mom missed during my childhood: 0.

The number of pairs of Mom’s socks I kept while cleaning out her dresser to wear on my own feet after she died: 13.

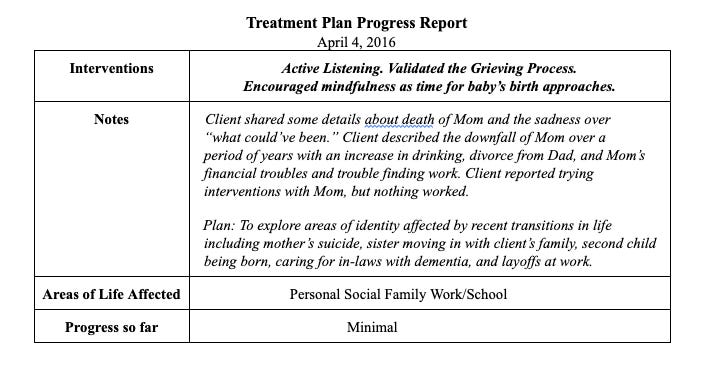

Jo, the counselor I saw on and off for fifteen years, retired right before my mom died. Jo had carefully held my story through my struggles to stay in some sort of relationship with my mother as she spiraled downward, through my many job transitions, and through the early stages of my infertility. And now she was not here to help hold the most painful story of my life. Twelve months after Mom dies, I finally summon enough energy to look for a new counselor. I am in the newly nauseous stage of early pregnancy, and each initial appointment becomes an Olympic feat -- researching insurance coverage, negotiating time off from my part-time job, arranging appointments while my two-year-old is at daycare.

Before Katie the Counselor, I tried many times to find someone. I really did. One counselor got excited about my understanding of God and went off on his own tangents about the afterlife, as if we were in a philosophy seminar. One counselor flinched and then tried to relax her face after I described how my mom died -- even though I sent preemptive emails to avoid the flinch. After recovering, she tried extra hard not to offend me by saying the wrong thing. If only there were speed-dating for counselors.

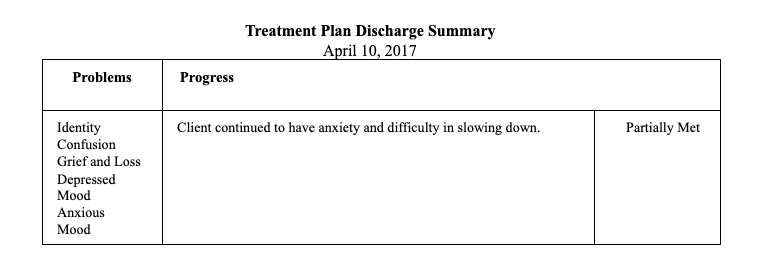

When she isn’t typing on a screen, I like Katie the Counselor, but I don’t love her. I just need someone to listen and not say something stupid. If not for the rating system, Katie could have met the bar.

Energy conservation. This is why I stay with Katie the Counselor for a year.

In Icelandic, there are multiple words for each number between one and four—depending on what is being counted and whether it is considered grammatically masculine, feminine or neutral. Flowers and money are feminine. Telephone numbers, cars and abstract counting are masculine. Houses, years, and time of day are neutral.

Is my anxiety feminine? Is my depressed mood neutral?

Other Numbers Katie the Counselor Did Not Ask Me About

Number of days of bereavement leave: 3.

Number of hours I slept the night before: 4.

Average number of times per day that I pick up my phone to text or call my mother and then have to remember (again) that she died: 7.

At 7:17p.m. on the Monday before Thanksgiving, 2014, time itself seems to freeze and then bend and morph. I watch myself, from outside myself, as I nurse Lydia, my one-year-old, rocking her to sleep in the navy-blue La-Z-Boy. After silencing my sister’s call by pushing the red button on my phone, I watch myself push the green button when she immediately calls back.

My baby shutters as the news travels through my bodily fluids and into her mouth. When she is unwillingly unlatched from my breast, I see my husband’s hands take hold of the news pulsing through our child’s screaming lungs. His arms carry her writhing into the bedroom. Then, I watch my whole body hit the floor and stay there for a long, long time. How many minutes? I don’t know. On a scale of one to ten, how loud are the screams? On a scale of one to ten, how much does it hurt? I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know.

According to linguistic researchers, the Pirahã tribe of the Amazon use only three words to count: one, two, many. The Pirahã word for one can sometimes mean roughly one. And the Pirahã word for two can sometimes mean not many.

More Numbers Katie the Counselor Did Not Ask Me About

Number of months my grieving sister had been living in our basement: 4.

Number of days my mother and older daughter were alive at the same time: 374.

Number of days my mother and my younger child will be alive at the same time: 0.

Almost Ten Years Later

This afternoon while watching television, Lydia, who is now 10, calls me over to snuggle with her on the cushy blue recliner in our basement family room. When she was a baby, Lydia and I basically lived in this chair, her body latched to mine. This was a chair for life’s basics—eating, sleeping, soothing. And now here we are —a perimenopausal mother and a prepubescent daughter—with our bodies understanding the need for connection, even though neither of us can speak it aloud. I sink my backside into the chair’s worn pleather, and let my daughter sink her purple camouflage stretch pants onto my mom jeans. Lydia’s thigh presses my hip tightly against the armrest, but I don’t complain because she rarely asks me to snuggle anymore. Instead, I wrap my arms around my daughter’s waist and savor the minty afterglow of her shampoo as she drapes her long limbs across my lap. She keeps her eyes fixed forward, scrolling past her usual documentaries about outer space, eclipses, and DNA, and landing on one called Zero to Infinity.

I am content to just hold her as she crunches her pretzel sticks and rests her head on my shoulder, blocking my view of the screen. The documentary host’s melodiously feminine voice floats into my ears, unembodied.

Zero and infinity were invented (or was it discovered?) after numbers were used for centuries.... Any number can be divided by any other number. Except zero. You cannot divide by nothing… There are multiple infinities. Some infinities are countable, and some infinities are not…

Lydia grabs another handful of pretzels, takes a swig of chocolate milk, and lays her head back on my shoulder. She keeps her eyes on the screen and scrunches her freckled nose in confusion as she digests the information. You cannot divide by nothing.

My gorgeous, growing daughter, who once lived inside me, is once again resting on my body. Part of her lived inside my body when I was inside of my mother before I was born. Part of my potential grandchildren have been inside of her since she was inside of me. She speaks to me through the gap between her two front teeth, the same gap that I had, and my mother had, and that all the women on my mother’s side had.

Mom! Multiple infinities! What does that even mean?

I have no answers. Only questions I wish I had been asked in a different way.

In this moment, how would I rate my tender gratitude?

More-than-three.

How would I measure my hard-earned joy?

Feminine. Roughly. Sometimes.

What number would I give my bittersweet melancholy?

There are multiple infinities. Some infinities are countable, and some infinities are not.

This is stunning. Thank you for sharing your grief and the growth that's come with carrying it.

Thank you for capturing and sharing